![]()

Image of an empty seat -- the early manner of dipicting the Buddha in images.

§

The Following is from "Silk Road: Religions: Buddhism" and is copyrighted and may not be reproduced except for personal use. This site has a great deal of information on the spread of Buddhism by way of the Silk Road.

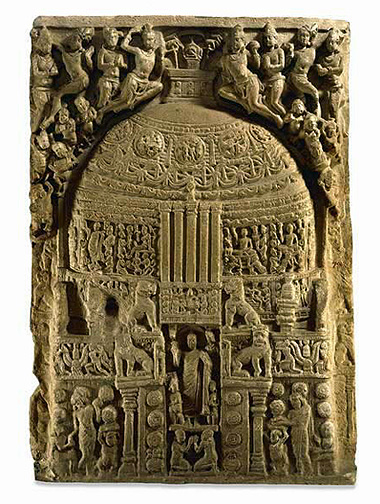

Stone relief carving

Side 1: Throne under the Bodhi Tree (1st century BCE)

Side 2: Great Stupa at Amaravati (3rd century CE)

From the Great Stupa at Amaravati

Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, India

Limestone

124.37 x 86.25 cm

Acquisition number: # OA 1880.7-9.79

This limestone slab has been carved on both faces. The earlier carving, which the British Museum dates to approximately the first century BCE, shows a group of worshippers paying homage to the location where Sakyamuni, the historical Buddha, received enlightenment. The two reliefs show an interesting dissimilarity, in that the later carving depicts the image of a Buddha standing in the entrance to the stupa, while the older carving only shows the Buddha's empty throne, a canopy and a pair of footprints marked with dharmachakras (wheels of law, a symbol of the Buddha's first sermon), all under the sacred bodhi tree where Sakyamuni sat at the moment of his enlightenment.

There are two prevalent explanations for the unusual subject matter found in the earlier carving. One scholarly opinion holds that illustrations such as this (commonly reproduced in early Buddhist art) are examples of "aniconic depiction," in which the presence of the Buddha is inferred by the throne, his footprints, or other attributes; in short, that these symbols signify the Buddha's presence despite his absence. Experts who hold this opinion argue that aniconic depiction probably resulted from rigorous strictures against creating image of the Buddha, since such images might promote idolatry and distract people away from the Buddha's message.

In certain instance (such as scenes clearly depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha), there can be no doubt that aniconic depiction is used. However, in scenes of a more general nature, an opposing view holds that such images should be interpreted quite literally - not as aniconic images of the Buddha, but depictions of important sites of Buddhist worship as they actually appeared at the time of carving. According to this explanation, the group of men depicted in this relief should not be interpreted as followers gathered around an aniconic Buddha, but as worshippers who pay homage and make offerings at the site of the Buddha's enlightenment.

The reverse side, which dates to the third century CE, shows the Great Stupa at Amaravati. A stupa is monument, originally intended to mark the site of internment of the mortal remains of the Buddha and his disciples. In later periods, stupas also served as places where sutras (sacred texts), relics and images were buried; they could also serve as purely symbolic structures. The veneration of stupas is expressed through circumambulating the dome-like structure in a clock-wise course. However, it is not the relics that are being worshipped; rather, the stupa serves as a focal point for the meditation ritual of circumambulation, and a reminder of the Buddha's message.

The style of the carving illustrating the Great Stupa is consistent with that practiced during the Satavahana dynasty (220 BCE-236 CE), the last group to provide royal patronage at Amarvati. It is believed this relief offers us an idea of what the Great Stupa would have looked like in the third century, and where sculptures and reliefs surviving in museum collections would originally have been placed. For example, a set of sculpted lions seated on pillars from Amaravati, very similar to those guarding the entrance to the stupa on this relief, may also be found in the collection of the British Museum.