[ Give Ear ]

Brahmi

Relative to the on-going discussion concerning the language used by the Buddha, and what, precisely, he intended by:

"... the much-discussed passage in the Culla-vagga (Vin II 139, 1-16) which tells how two bhikkhus complained that the Buddha's audiences were spoiling his utterances sakāya niruttiyā, and asked the Buddha if they could translate his sermons chandaso, but were forbidden to do so. It is not clear what they were proposing to translate into ..."[1]

My reading of the passage was that not only did the bhikkhus wish to translate the suttas, but to write them down.

I have been doing a little looking into the understanding of writing at the time of the Buddha. It is clear that writing was well known in the area. Word is that Pāḷi was first written in a script known as Brahmi. This is the script to which virtually all Indo European scripts are related. It, itself, may have had roots in either or both of two earlier scripts: Indus Valley Script, and Semitic scripts; and there is another theory, of course, which says it was developed on its own.

Check out the credit link for this picture of an Asokan edict (in Brahmi) for a massive site on ancient languages and scripts.

Used with permission: http://www.cs.colostate.edu/~malaiya/scripts.html

The Edicts of King Ashoka An English rendering by Ven. S. Dhammika

On page 131 of Professor Rhys Davids' Buddhist India (see References below for other related chapters), he makes the off hand comment that what we really have in the early writing of Brahmi is a syllabary, not an alphabet. But this is just what I have been suggesting all along is the case with the Pāḷi, only without the implication that this is somehow a limitation.

The way I learned Pāḷi (what you get here and there on BuddhaDust as "Old Pāḷi") was that what we are today hearing as words was at one time (I believe not yet entirely out of consciousness by the time of the Buddha) considered to be what we would call a sentence. In other words there were no double consonants, or groups of consonants or word endings because each "letter" was pronounced and heard separately.

For example, we say: Appamāda means: "don't be careless", or "non-carelessness": a + pamada. But track this word through the Suttas and you will see that it carries far more weight than just this meaning. What we have in this word is a "story" (actually many many stories) and it is the "moral of the story" that has come down to us as the meaning of the word.

a pa ma da

The first syllables every human born hears.

a = one, a, single, to, for, at, satisfaction, question, understanding, against, out, there, this, that, here ...

ap = up

p-pa = Bang, Pow, Boom, Pt'uii and also father

ma = made, mothered, -ing-a; backwards: m = ing, on-go-ing-ing

da = father, this dat that

Ah!

A?

A pa.

A pa?

A pa ma.

M~a?

D-a.

Da a?

A pa ma da adam appa.

A cautionary tale!

The thesis suggested here concerning the language of the Buddha is that all the words chosen by The Buddha, from those words available to him at the time, whatsoever those languages may have been called, were those words that had roots back to the time when this business of syllables equaling words was the case with all words.

Further, it is being proposed that this was done with a purpose. The purpose was that these words are heard by all men in a similar way because they relate to sounds heard in nature, or sound like their meaning [onomatopoeia]. This being the case, the Dhamma could be picked up, studied, and understood by someone who had no knowledge whatsoever of Pāḷi.

Now you may be thinking of some student sitting down in some library with a Pāḷi book and a piece of scratch paper figuring out the Dhamma. This is not exactly the way I see it. There are mental states which are attained by seekers that are very powerful in scope. There are many stories in the literature of Eastern religions which speak about people who have stumbled onto trance states and found themselves speaking languages they know they never learned. These people have found accidentally what is attainable deliberately: high mental states in which it is possible to say that the words approach one and instruct one of their own accord ... actually, where all knowledge is avaiable just for the paying attention to it. Today we hear of people who talk to plants ... something like that. The intellectual barriers are down, the usual objections are not pulling the blinders down and this powerful mind is able to understand. It is to those who, because of making such an effort as brings them to these high states that this Dhamma, constructed as I am suggesting, yields its meaning apart from the grammar books.

I am not saying that The Buddha ignored conventional speech, I am saying that what we have in the Dhamma is something that can be heard at more than one level; Rhys Davids had his finger right on the doorknob of the 'nother level, but his academic bias made him think that that which was claimed by the academics as an advance in writing was also an advance in communication. I suggest that what we see in the way Rhys Davids dealt with this is proof of the contrary.

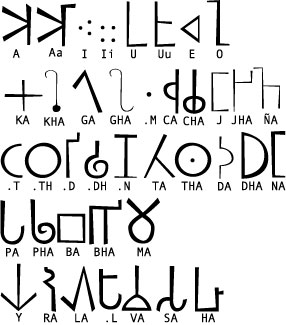

American Brahmi Script

This is the result of an abandoned idea of putting together an "American Brahmi" font. As well as the characters shown in this image, the character set would need to be able to modify each consonant for "vowel indicators" (each consonant has the intrinsic vowel "a" and is modified for other vowel sounds by connecting lines from the top, middle, or bottom, left or right) and double consonants would each need their own glyph (double consonants were formed by merging two glyphs — how, exactly, is uncertain to me, and it was apparently not always done in early versions of the script, and done in different ways at different times). The number of characters which need to be created exceed the capacity of most keyboards out there. Madness to use ... and, in any case, as I said elsewhere, my reading of the famous "translation" episode documentated in the Vinaya was that the Buddha objected to his suttas being put down in this script ... that there is, in fact, an "error of wrongdoing" connected to doing so even for one syllable. (... just an aside, really, that rule was for bhikkhus, and my guess is it had less to do with the idea of writing it down than it did of directing the bhikkhus to paying attention to what was the most important thing: accomplishing the goal ... although I can imagine the people of the day editorializing across the back fence about this "writing" stuff being the forerunner of the ultimate corruption of their youth).

From: E-sangha, Buddhist Forum and Buddhism Forum > The Academy > Pāḷi Forum

My questions are:

1. What does the original Pāḷi script look like?

2. Where are there online examples of it?

3. Is there an online Tipitaka in the original Pāḷi script?

1. What does the original Pāḷi script look like?

Since Pāḷi emerged in the days of oral culture, it does not have an 'original' script.

For examples of modern scripts, see

Gandhari Tipitaka texts were written in Kharosthi script http://www.omniglot.com/writing/kharosthi.htm

Edicts of Emperor Asoka http://www.cs.colostate.edu/~malaiya/ashoka.html and the inscription on the Piprahwa urn with relics of the Buddha, were written in Brahmi script http://www.omniglot.com/writing/brahmi.htm

You can request a free CD-rom with the compelte Pāḷi canon in seven scripts at Vipassana Research Institute:

The seven scripts or fonts are: Roman, Myanmar, Devanagari, Thai, Sinhalese, Khmer, Mongol.

2. Where are there online examples of it?

Brahmi script

3. Is there an online Tipitaka in the original Pāḷi script?

No. [More recently, a version of the Majjhima Nikaya, was set in Imperial Brahmi by the Theravada Pipitaka Press — www.nibbanam.com] If you wanted you could make one by downloading one of the Brahmi fonts from the website above, learning the script, and then downloading the VRI Tipitaka and using your wordprocessor's search-and-replace function to make the necessary changes so it will display properly.

The site owner, Eisel Mazzard, is a Canadian Pāḷi scholar whose vocation in life is to put Pāḷi texts into scripts that nobody can read. He is especially enthusiastic about the Brahmi script.

Best wishes, Dhammanando Bhikkhu

Interesting article:

§

Of Brahmi Script: A Linguistic Approach

Abstract

Dilip Rajgor

Brahmi script is considered to be the earliest known script of early historic India. Archaeological evidences indicate that the inscribed artifacts of this period can be dated to as late as third century B.C. Furthermore, it has been opined by archaeologists that Brahmi is a derivative of a Semitic prototype.

However, the present linguistic analysis of the said script forwards a different profile. Accordingly, it has been suggested that the evolution of Brahmi as a script was a slow and gradual process. This evolution can conveniently be classified into five different phases. These are:

(i) Harappan Script (c. 2500 - 1700 BC),

(ii) Proto-Brahmi Script (c. 1700 - 600 BC),

(iii) Pre-Mauryan Brahmi Script (c. 600 - 350 BC),

(iv) Mauryan Brahmi Script (c. 350 - 150 BC), and

(v) Post-Mauryan Brahmi Scripts (c. 150 BC - A.D 600).

On the basis of the proposed linguistic theory of evolution, it has been argued that the linguistic design of Brahmi was a product of the phonetic-phonological-grammatical work done by Indian scholars over a period of a few centuries.

Introduction from cave paintings to computer languages, human beings have made a commendable progress. During this developmental process, two landmarks stand apart: first, the development of language; and second, the invention of writing. The writing system evolved over a period of thousands of years from pictographs to alphabetic scripts, and now the most sophisticated computer languages. Though we still use the alphabetic scripts throughout the world, this system of writing is yet not perfect.

The evolutionary process of script in India can be traced back to pre-history where we find cave paintings at sites like Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh and Tarsang in Gujarat. Leaving aside the pictographs of these caves, India witnessed a sudden growth in the writing system. This appears in the Mature Harappan period during c. 2500-1900 BC. This undeciphered Harappan script suddenly appears in the Indian protohistoric horizons, stays there for about seven hundred years and miraculously disappears in the dark pages of history only to be discovered after three thousand eight hundred years. From about 1700- 250 BC, no evidence of any writing system is encountered in ancient India. Then suddenly, like the Harappan script, emerges Brahmi script in the third century BC. Fortunately, since the reign of Mauryan emperor Asoka (c. 250 BC) continuous evidence of writing system is known to exists in the form of various styles of writing Brahmi known as Mauryan or Asokan Brahmi, Ksatrapa Brahmi, Gupta Brahmi and so on.

Evolution It can be observed from the Fig. 1 that the first and the third letters of each phonological type or varga of the consonants, i.e., the unaspirated sounds, and the three basic vowels have independent or primary shapes. The presence of only two aspirated letters out of ten among the primary forms, suggests that these are not the part of the earliest Indian alphabet, which did not express aspiration, though independent in shape, they may have been invented by the grammarians who perfected the alphabet (Upasak 1960).

The inclusion of the two aspirated consonants, viz., /gh/ and /jh/, should have been done when there were no aspirated consonants at all, as they are totally independent forms in the Mauryan Brahmi. However, the rest of the eight derived aspirated consonants were included in the later period. As far as the vowels are concerned, the three basic vowels gave rise to seven derived vowels viz., /a/, /i/, /u/, /e/, /ai/, /o/, and /au/. The anusvara was a later addition, as it is not derived directly. Similarly, the visarga was a still later addition in the post-Mauryan period that is included in the Ksatrapa Brahmi. Hence it appears that the evolution of Brahmi was in four stages preceded by the Harappan script (Rajgor 2000).

(i) Harappan Script (c. 2500 - 700 BC),

(ii) Proto-Brahmi Script (c. 1700 - 600 BC),

(iii) Pre-Mauryan Brahmi Script (c. 600 - 350 BC),

(iv) Mauryan Brahmi Script (c. 350 - 150 BC), and

(v) Post-Mauryan Brahmi Scripts (c. 150 BC - AD 600).

i) Harappan Script (c. 2500 - 1700 BC)

Harappan script that is also known as the Indus script appears on the horizon of the Indian subcontinent from c. 2500 to about 1700 BC. Approximately four thousand Harappan texts are known consisting mostly of seal impressions. This undeciphered script is supposed to have been written from right to left (Parpola 1994). Nearly four hundred different signs were employed in inscribing the Harappan language. Though nothing conclusive is known about the final decoding of the Harappan script, it seems quite probable that this script was logosyllabic (Parpola 1994).

It is a matter of speculation to presume that Brahmi script was evolved from the Harappan script. This is mainly due to the fact that the former is an alphabetic script whereas the latter is a logosyllabic script. Furthermore, there is a wide gap of about one thousand five hundred years between the fall of the Harappan script and rise of the Brahmi script.

ii) Proto-Brahmi Script (c. 1700 - 600 BC)

With the final disappearance of the Harappan script in c. 1700 BC, a wide gap of about one thousand five hundred years is noticed in Indian archaeology where not a single example of written records is encountered. Though no geometric forms are available of a script during this period, it is possible that experiments were carried away to form the Proto-Brahmi script.

The Proto-Brahmi script should have minimum vowels including the three basic vowels, viz., /a/, /i/, and /u/. A list of consonants should look like: /k/, /g/, /c/, /j/, /t/, /d/, /t/, /d/, /n/, /p/, /b/, /m/, /y/, / r/, /l/, /v/, /s/, and /h/. However, to supplement this linguistic reconstruction, archaeological evidences are awaited.

iii) Pre-Mauryan Brahmi Script (c. 600 - 350 BC)

During the sixth century BC, with the decline of the tribal organization of the society and the growth of towns, trade, and commerce, there arose a distinct cognitive change. At that period of time there was a very marked tendency towards doubt and dissent and free speculation (Verma 1979: 104). Hence the use of writing in the age of the Janapadas (States) was related to the social, religious, economic, political, and cognitive changes. This ultimately resulted in the need for a better writing system that could encode the spoken language more precisely.

Hence in the Pre-Mauryan Brahmi, certain additions took place. In this phase, some vowels evolved from the basic vowels, which could have been /a/, /i/, /u/, /e/ and /o/. In the list of consonants, twelve consonants were added. Hence the number of vowels increased to eight, and the consonants to thirty. The vowels were: /a/, /a/, /i/, /i/, /u/, /u/, /e/, and /o/. The consonants were: /k/, /kh/, /g/, /gh/, /c/, /ch/, /j /, /jh/, /t/, /th/, /d/, /dh/, /n/, /t/, /th/, /d/, /dh/, /n/, /p/, /ph/, /b/, /bh/, /m/, /y/, /r/, /l /, /v/, /s/, /s/, and /h/.

Unfortunately, not a single example of Pre-Mauryan Brahmi has been excavated in India. Nevertheless, it is known from the evidence of the Kharoshthi script (Ojha 1918) that at a particular point of time in the pre-Asokan period, the Kharoshthi script followed such a linguistic theory. In the said script, the number of vowels were only six, namely /a/, /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/ and /am/.

Though the evidence of Mauryan Brahmi script in India does not go beyond c. 250 BC, recent excavations at Anuradhapur in Sri Lanka have revealed earlier evidences of Mauryan Brahmi. These are inscribed potsherds, which are dated to c. 400 BC by the C14 dating method (Allchin 1997). The topography of the recent inscriptions is similar to the Mauryan script. However, the only difference reported is the crude forms in Sri Lanka, which are similar to those on the Piprahwa vase inscription. This implies that by 400 BC, Sri Lanka, and for that matter, the Indian subcontinent was already literate enough to read and write.

iv) Mauryan Brahmi Script (c. 350 – 150 BC)

Mauryan Brahmi script in the third century BC, i.e., during the reign of Maurya emperor Asoka, appears to be a well-established alphabetic script with as many as eleven vowels and thirty-four consonants. In this script, the knowledge of the phonetic rules of Sanskrit is well manifested. Here one finds seven derived vowels with an anusvara, and thirteen derived consonants including eight aspirates (Fig. 1). It appears that the derived forms numbering to twenty-one got their shapes from the early Sanskrit grammarians like Yaska, who perfected the Sanskrit alphabets. Upasak (1960) has rightly argued that in course of this perfection, the early Sanskrit grammarians accepted those letters that already existed and evolved the new shapes, either basing them upon previous forms or coining them independently to suit their purpose. In the form in which we have the Brahmi alphabets, it is the work, not of merchants, but of learned men who had knowledge of grammar and Sanskrit phonetics.

v) Post-Mauryan Brahmi Scripts (c. 150 BC - AD 600)

The evolution of Brahmi script did not end in the Mauryan period, nor did the Mauryan Brahmi was perfect. In the post-Mauryan period, vowels like /h/, /r/ and /l/ were added to the script. The earliest example of /r/ is found on the inscription of Castana - Rudradaman I at Andhau in Kutch, Gujarat (Mirashi 1981). Interestingly, a manuscript called Usnisavijayadharani dating back to the sixth century AD was discovered at a monastery called Horyuji in Japan (Ojha 1918). At the end of the said manuscript, a complete list of all the letters is given. It includes sixteen vowels: /a/, /a/, /i/, /i/, /u/, /u/, /r/, /r/, /l/, /l/, /e/, /ai/, /o/ , /au/, /am/ and /h/. The manuscript is worth noticing as it is the earliest evidence depicting separate forms of four rare vowels: /r/, /r/, /l/ and /l/. Hence, it can be concluded that the evolution of Brahmi was a continuous process, beginning with the Proto- Brahmi script through the Post-Mauryan Brahmi scripts like Ksatrapa, Gupta and Kutila Brahmi scripts (Fig. 2).

Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be observed that the evolution of Brahmi as a script was a slow and gradual process. It can further be argued that the linguistic design of Brahmi was a product of the phonetic-phonological-grammatical work done by Indian linguists over a period of a few centuries. In the evolutionary process, the Harappan script did influence the evolution but it is not certain whether the Harappan script ever served as a prototype for the successive Brahmi script. However, it is very clear that the fall of the Harappan script must have forced the intelligent minds of the post-Harappan period to invent a better way of expression, namely Brahmi script.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks are due to Prof. P. G. Patel of the University of Ottawa, for encouraging me to carry out the linguistic research of Brahmi script. I am also grateful to Dr. P. K. S. Pandey of the M. S. University of Baroda for guiding me during the research endeavor.

References

Allchin, F. R. (1997). Personal Communication.

Bhattacharya, Harendra K. (1959). The Language and Scripts of Ancient India. Calcutta: Bani Prakashani.

Bright, William (1990). Written and Spoken Language in South Asia. In his Language Variation in South Asia. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 130-47.

Buhler, George (1882). On the Origin of the Indian Alphabet and Numerals, Indian Antiquary, vol. XI, p. 268.

Buhler, George (1896). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Studies, reprint.

Buhler, George (1904). Indian Palaeography. Pathe: Eastern Book House, reprinted in 1959 (first published in Indian Antiquary).

Burnell, A.C. (1878). Elements of South Indian Palaeography. London.

Crystal, David (1987). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cunningham, A. (1854). The Bhilsa Topes or Buddhist Monuments of Central India. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

Cunningham, A. (1877). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicaram, vol. I - Inscriptions of Asoka. Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing.

Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1986). Indian Palaeography. Delhi : Munshiram Manoharlal (first published in 1963).

Daniels, Peter T. and Bright, William (Eds) (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford; Oxford University Press.

Diringer, David (1969). The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind. New York: Funk and Wagnallas, 3rd ed.

Gelb, I.J. (1963). A Study of Writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, revised.

Goyal, S.R. (1979). Brahmi - An invention of the early Mauryan period. In Gupta and Ramachandran (1979).

Gupta, S.P. and Ramachandran, K.S. (Eds) (1979). The Origin of Brahmi. Delhi : D.K. Publications.

Hultzsch, E.(1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. I - Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Government of India.

Jensen, Hans (1970). Sign, Symbol and Script - An Account of Man's Efforts to Write. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 3rd ed.

Jha, Amiteshwar and Rajgor, Dilip (1994). Studies in the Coinage of the Western Ksatrapas. Nasik : Indian Institute of Research in Numismatic Studies.

Mahalingam, T.V. (1967). Early South Indian Palaeography. Madras: University of Madras Press.

Mahulkar, D.D. (1980). The Pratishakhya Tradition and Modern Linguistics. Baroda: M.S. University of Baroda Press.

Mahulkar, D.D. (1990). Pre-Paninian Linguistics. Delhi: Northern Book Center.

Mehendale, M.A. (1948). Asokan Inscriptions in India: A Linguistic Study. Bombay: University of Bombay.

Mirashi, V.V. (1981). The History and Inscriptions of the Satavahanas and the Western Ksatrapas. Bombay: Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture.

Ojha, G.H. (1918). Bharatiya Prachin Lipimala. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal (Hindi). Reprint. First edition 1894. Udaipur: Sujjain Press.

Pandey, Rajbali (1952). Indian Palaeography. Varanasi: Motilal Banarasidas, Part I. (Reprint, second edition 1957)

Parpola, Asko. (1994). Deciphering the Indus Script. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parpola Asko. (1996). The Indus Script. In Daniels and Bright (1996), pp. 165-171.

Parikh, P.C. (1974). Gujaratman Brahmithi Nagari Sudhino Lipivikas (I.sha. 1500 sudhi). Ahmedabad : Gujarat University (Gujarati).

Patel, P.G. (1993). Ancient India and the current orality- literacy divide theory. In R.J. Scholes (ed), Literacy and Linguistic Analysis, pp. 199-208. Hillsdale, N.J: Erlbaum.

Patel, P.G. (1995). Brahmi Scripts, orthographic units and reading acquisition. In I. Taylor and D. Olson (Eds), Scripts and Reading: Reading and Learning to Read World's Scripts, pp. 265-75. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Patel, P.G. (1996). Linguistic and cognitive aspects of the Orality- Literacy complex in Ancient India. Language and Communication, vol. 16, pp. 315-29.

Rajgor, Dilip (2000). Palaeolinguistic Profile of Brahmi Script. Pratibha Prakashan. Delhi. (Forthcoming).

Sivaramamurti, C. (1952). Indian Epigraphy and South Indian Scripts. Madras: Bulletin of the Madras Govt. Museum.

Upasak, C.S. (1960). The History and Palaeography of Mauryan Brahmi Script: Patna: Nava Nalanda Mahavihara.

Verma, T.P. (1971). The Palaeography of Brahmi Script in North India. Varanasi: Siddharth Prakashan.

Verma, T.P. (1979). Comments on Goyal's paper: Brahmi - An invention of the early Mauryan period. In Gupta and Ramachandran (1979), pp. 98- 110.

Walawalkar, A.B. (1951). Pre-Ashokan Brahmi: A Study on the Origin of Indian Alphabet. Bombay: Muni Brothers.

Fig. 1: Basic and Derived Letters in Mauryan Brahmi (Upasak 1960)

(c. 250 BC)

[1] The dialects in which the Buddha preached, H. Bechert (ed.): The Language of the Earliest Buddhist Tradition, Gottingen 1980, pp 61-77 ... I am reading from a photocopy of a revised version from this source which has no identification.

References:

See also: Indo-European Languages

and

Translation Bias

The Chapters from Rhys Davids: Buddhist India, that deal with language and literature:

Writing -- The Beginnings

Writing -- Its Development

Language and Literature -- General View

Language and Literature -- The Pāḷi Books

For information on ancient scripts:

http://www.ancientscripts.com

Bibliography: Language in Early Buddhism and Other Articles of Interest in Buddhist Studies