Original Sources

Examining the Definition and Constructive Use of Original Sources in the Study of Buddhism

It is an encouraging phenomena to see the emergence of a debate on the usefulness of original sources in the study of Buddhism. At this time some may find it useful to examine what it means to 'go to the original sources' and how, once found, they should be used.

What is an original source?

The very first thing that must be determined has nothing to do with one's research tools, it is:

What are you looking for?

Let us take the case of some person interested in researching psychology.

Are you investigating this subject because you experience periods of great unhappiness, depression and un-ordinary mental phenomena and suspect that this indicates that you are 'mad' and because you have heard that psychology has all the answers?

Is your intent to practice psychology as origianlly taught?

Or were you talking about psychoanalysis?

Or psychotherapy?

Or Freudian psychoanalytic psychotherapy?

Which psychology? Freudian? Yungian? Reichian? Primal Scream? Etc.? There are now quite a number, each claiming to be the most efficient at dealing with issues that are not entirely clear.

Freudian psychoanalysis as it was originally taught?

or are you interested in the history of psychology?

or are you interested in any sort of practice that will give you a piece of paper stating that you are an authority so that you will be able to charge high fees for your otherwise useless practice of what you have learned from secondary sources?

Or maybe you are the sort that just likes to go around beating other people over the head taking issue with whatsoever position they may hold?

Taking just the case where someone is interested in determining exactly what it was that Freud taught when he taught what became psychoanalysis, what is not an original source is the pronouncement of some teacher quoting a textbook that teaches Freud's various theories concerning human psychology. The original source in this case is Freud's writing on various theories concerning human psychology. Once one has read Freud's own words on the subject, commentary, aka 'advances in the subject taking into consideration the higher wisdom of modern scientific methodology,' may or may not prove to be interesting perspectives.

But what is Freud's writing? Is Freud's writing the translation of it? Or must one return to the German? Or does one need to examine the hand-written manuscript from which the printed version was produced? Or must one ... or may one consult with Freud himself through extra ordinary means? Suppose he doesn't remember. If one has consulted Freud himself through extra-ordinary means, is this something that one can rely on for one's self? Claim as an authoritative view to others?

We can go further in another way: Freud's thinking was, for the most part, not original with him. He took the germ of his ideas from Frederick Nietzsche,[1] who took the germ of his ideas from Schleiermacher,[2] Schleiermacher took the germ of his ideas from Kant, Kant took the germ of his ideas from Spinoza, Spinoza took the germ of his ideas from what he knew of Gotama the Buddha. We see this clearly in the writings of Nietzsche who discusses Buddhism directly and with great admiration. [I have no idea if this etiology is really true or not, this was just the third and fourth-hand knowledge I was taught by my Philosophy 101 Professor at Bard, and since I was drunk or hung-over or playing footzie with one of the female students most of my time there even this may have been learned incorrectly. ... you hear? ... and, please, let us just skip over the part where Professor Khulman or one of his students that was paying attention writes in to tell me how it 'really' went.]

Where, if we should draw a line, should the line be drawn?

What was your interest in the first place?

That is the point. The definition and usefulness of 'original sources' is relative to your goal.

If your intent was to learn what Freud himself taught, it might be necessary to trace sources back to where at least going back any further would lead to the need to have been Freud himself.

If your intent was to investigate Freud because of a belief that in investigating his work you will discover a practice that will eliminate your unhappiness and depression and doubts concerning your experience of un-ordinary mental phenomena, you will need to find and research original sources only to the point where you have satisfied your original need or have determined that no satisfaction of that need is to be found in that pursuit.

If your intent was to discover what it was that Freud himself taught and to determine whether or not what he taught was well-taught, you may be out of luck because to determine precisely what was taught might push you to the point where you would need to be Freud to be sure and to determine whether what he taught was well-taught or not (that is, effective in accomplishing what was stated as what was to be accomplished by the system) you might need to have first-hand experience in the problems he was attempting to solve. Do you think you could rely on the statements of mad persons claiming to have been cured by his methods? How would they know? Do they have MDs? PhDs? Did they do research into the original documentation to the point where they became Freud himself?

That's the second thing: you need to understand that there are limits to knowing and seeing that should always be taken into consideration when discussing what one knows and sees or what someone else knows and sees.

It is an interesting corollary that understanding that last point one could not rely on the method of Freud for the accomplishing of the goal of curing madness unless it were the case that Freud was himself mad. In that case we would need to consider whether or not we could take the word of a madman.

I think this is a marvelous revenge on Freud for his Catch 22 that if you deny you are mad, you are mad.

It is because there are unreliable sources of information that original sources need occasionally to be used.

It is not a reliable method to have faith in the statement that a goal can be attained if it is made by a person who has not attained that goal.

To use one of my old saw similes: Watch out for the man who teaches how to quit smoking who still, himself, smokes, and says: 'I can quit any time.'

§

Then there is the case where one can know and see with certainty and without faith. When one has the goal of going from one place to another place that is known (e.g. a certain house address on a certain street in a certain town ...), researching the original documentation, determining the method for going from the one place to the other known place, following the method and arriving at the known place that is the goal one can be certain that the method, whether found in the original documentation or in commentary is a correct method and that further investigation is not needed.

In the case of a known goal one only needs to uncover original documentation as to how to achieve that goal to the point where one following the method found there works.

At the point of having achieved a goal, it can often, but not always, be seen whether or not arriving at the goal was achieved exclusively by having followed the method or could have been achieved by some other or many other methods or even by not following any method because although unknown at the time arriving at the goal was inevitable.

There is a side-track which should be avoided: It is not reliable in determining whether or not a method works in achieving its stated goal to review its success in other people. A method may be correct and everyone following it may be practicing it incorrectly. That is not the fault of the method, it is the fault of the practitioner who practices it incorrectly.

You can lead a horse to water, but you can't make her drink.

I can only point the way.

— Gotama, The Awake

"In the case where the teacher teaches a wrong doctrine, it is the student who does not learn that is praiseworthy, the teacher blameable, the student who learns that is blamable;

In the case where the teacher teaches a correct doctrine, it is the student who learns that is praiseworthy, the student who does not learn that is blameable, the teacher praiseworthy."

— Gotama, The Awake

This is a good case for the usefulness of original sources: Is everyone practicing incorrectly? What is the method as actually stated? Here the researcher need go back no further than to the point where the error in practice is seen. At that point a new cycle of actual practice would be the effective strategy.

It is equally unreliable to follow a method simply because a great number of people follow the method and proclaim it as the reason they have achieved the solution to the problem you are seeking to solve. That is a good reason to investigate, not a good reason to follow without determining at least that there is an exact correlation between the problem the method itself states it will solve and the problem the followers are saying they have solved. A great number of people can follow a system that is completely alien to the beliefs of the people following it.

We are not discussing here beating people over the head for their stupidity. This is especially so for those who would follow the method of Gotama as taught in the original documentation. This is a system where the highest principle is 'upekkha' detachment. It would be the man who still smokes teaching how to quit smoking for a Buddhist following the method found in the original documentation to teach beating people over the head to get them to follow the method (i.e., 'I will renounce attaining the goal for myself until such a time as all beings are able to attain the goal with me.') If you don't believe me, read the original documentation. How far into the original documentation will you need to go to find the statements that support this statement? Here. This is the original statement:

This is pain.

The origin of this pain is thirst.

To end the pain, end the thirst.

If you can see the logic at this level, you know that the statement made is true. If you cannot see the logic because you are unwilling to invest your mental effort in a case where it may be a waste of time because it could be wrong, go back a level. Translations will reveal that this statement is made early and often throughout the Dīgha Nikāya, Majjhima Nikāya, Anguttara Nikāya, and Saṁyutta Nikāya, not to mention nearly every commentary that has ever been written about Buddhism.

If you are a true skeptic, look up the Pāḷi.

Idaṁ kho pana bhikkhave, dukkhaṁ ariyasaccaṁ:|| ||

Jāti pi dukkhā,||

jarāpi dukkhā,||

vyādhi pi dukkho,||

maraṇam pi dukkhaṁ,||

sokaparidevadukkhadomanassupāyāsā pi dukkhā,||

appiyehi sampayogo dukkho,||

piyehi vippayogo dukkho,||

yam picchaṁ na labhati tampi dukkhaṁ,||

saṅkhittena pañcupādānakkhandhā dukkhā".|| ||

Idaṁ kho pana bhikkhave, dukkhasamudayo ariyasaccaṁ:|| ||

"Yāyaṁ taṇhā ponobhavikā nandi rāgasahagatā tatra tatrābhinandinī,||

seyyathīdaṁ:|| ||

Kāmataṇhā,||

bhavataṇhā,||

vibhavataṇhā".|| ||

Idaṁ kho pana bhikkhave, dukkhanirodho ariyasaccaṁ:|| ||

Yo tassā yeva taṇhāya asesavirāganirodho cāgo paṭinissaggo mutti anālayo.|| ||

Idaṁ kho pana bhikkhave, dukkhanirodhagāminī paṭipadā ariyasaccaṁ:|| ||

Ayam eva ariyo aṭṭhaṅgiko maggo,||

seyyathīdaṁ:||

sammā-diṭṭhi,||

sammā-saṅkappo,||

sammā-vācā,||

sammā-kammanto,||

sammā-ājīvo,||

sammā-vāyāmo,||

sammā-sati,||

sammā-samādhi.|| ||

'Yaaggg!' What is that supposed to mean?

Here is my translation:

Here then, beggars, this is the aristocrat of truths with regard to pain:

Birth is pain,

aging is pain,

sickness is pain,

death is pain;

grief and lamentation,

pain and misery,

and despair are pain;

being yoked to the unloved is pain,

being separated from the loved is pain

Not getting the desirable, that too is pain.

To be concise:

the five shitpiles binding up individuality are pain.

This, beggars, is the aristocrat of truths with regard to the origin of pain:

it is in whatever thirst results in living; delight; lust for getting; seeking delight now here now there;

it is just as well to say it is:

thirst for pleasures,

thirst for living,

thirst for escape.

This, beggars, is the aristocrat of truths with regard to the end of pain:

it is in the passing out,

the rejection,

the doing away with,

the ending with nothing remaining of that lust.

This, beggars, is the aristocrat of truths with regard to the way to get to the end of pain:

it is this aristocratic eight-dimensional high way:

high view,

high principles,

high works,

high lifestyle,

high reign,

high mind,

high get'n high.

If you still have doubts, no problem! Look up the individual words in The Pāḷi English Dictionary or Childers A Dictionary of the Pāḷi Language, or in Cone, A Dictionary of Pāḷi, review the dozens of other translations of this bit of Pāḷi.[3] This is 'original research into the original documentation.' This is commendable. Recommendable. Dependable. ... up to a point.

Even to this point it is not reasonable to assert the truth of a thing because research into original documentation shows that the results have been reliably reproduced by others. 'The commentaries are the real truth because they were written by Arahants and have been subjected to testing for more than a thousand years.' A thousand years of testing can result in incorrect results if the testers are fools or frauds or self-deluded or if what is being tested is one thing and what is being researched (what was originally taught) is another.

If you cannot relate the words here to actual personal experience you will need to take another step. You will need to follow the method as hypothetically true. You need to see for yourself if you can reproduce the reported results. It will only be then that you will know for yourself.

The point? Original research into original documentation has limits and many many pitfalls.

§

Here on this site the assumption being made is that the reader is seeking in the method taught by Gotama, a method for the solution to the problem of pain as they experience it for themselves from the pain of rebirth, aging, sickness and death, grief and lamentation, pain and misery and despair; from the pain of not getting what is wanted to getting what is not wanted, to the ultimate understanding that whatever there is that is own-made, that constitutes a living, existing being, that is body, sensation, perception, own-making and individualized consciousness is, in a word, pain.

It is being assumed that this seeker has 'listened' to the claims being made in the world by various schools of thought with regard to the solution of that problem.

It is assumed only that this seeker has determined that an investigation of what Gotama taught, now known as 'Buddhism' is a possible candidate for serious examination of the possibility that it may, in fact, hold a solution to this problem.

Consequently, here on this site the effort is being made to present Gotama's system for the eradication of pain, dukkha, as he has defined it, himself, in the original sources and in commentary and dialogs where the original sources are defined as and limited to the Dīgha Nikāya, Majjhima Nikāya, Anguttara Nikāya, and Saṁyutta Nikāya in translation or in the original Pāḷi as found in the Pāḷi Text Society Pāḷi Texts where there is confusion or doubt concerning the meaning. It is allowed that although it has not yet happened, that there may be a disparity of significance between versions of the Pāḷi. And it is being pointed out that, because of that, there is a limit to the usefulness of research into what was taught, that in order for the truth to be determined without doubt it will be necessary to put the system into practice with the assumption that it is true to the best extent of one's research at least hypothetically. With practice will come results. With results will come the opportunity to evaluate. With evaluation will come progress. With progress will come clarity.

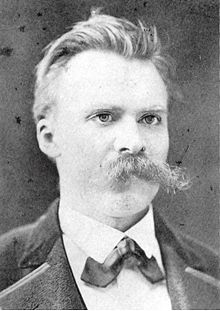

[1] Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche. German: October 15, 1844 — August 25, 1900) was a German philosopher, poet, composer, cultural critic, and classical philologist. He wrote critical texts on religion, morality, contemporary culture, philosophy, and science, displaying a fondness for metaphor, irony, and aphorism.

[2] From Wikipedia: Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (German: November 21, 1768 — February 12, 1834) was a German theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar known for his attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Enlightenment with traditional Protestant orthodoxy. He also became influential in the evolution of Higher Criticism, and his work forms part of the foundation of the modern field of hermeneutics. Because of his profound impact on subsequent Christian thought, he is often called the "Father of Modern Liberal Theology" and is considered an early leader in liberal Christianity. The Neo-Orthodoxy movement of the twentieth century, typically (though not without challenge) seen to be spearheaded by Karl Barth, was in many ways an attempt to challenge his influence.