PSALMS OF THE SISTERS

LXIV

Uppalavaṇṇā

SHE, too, was born, when Padumuttara was Buddha, at the city Haṇsavati, in a clansman's family. And, when grown up, she heard, with a great multitude, the Master teach, and assign a certain Bhikkhunī the chief place among those who had mystic potency.[1] And she gave great gifts for seven days to the Buddha and the Order, and aspired to that same rank. ...

In this Buddha-age, she was reborn at Sāvatthī as the daughter of the Treasurer. And because her skin was of the colour of the heart[2] of the blue lotus, they called her Uppalavaṇṇā.[3] Now, when she was come of age, kings and commoners from the whole of India sent messengers to her father, saying: 'Give us your daughter.' Thereupon the Treasurer thought: 'I cannot possibly meet the wishes of all. I will devise a plan.' And, sending for his daughter, he said: 'Dear one, are you able to leave the world?' To her, because she was in her final stage of life, [112] his words were as if oil a hundred times refined had anointed her head. Therefore she said: 'Dear father, I will renounce the world!' He, honouring her, brought her to the Bhikkhunīs' quarters, and let her be ordained.

A little while afterwards it became her turn for office in the house of the Sabbath.[4] And, lighting the lamp, she swept the room. Then taking the flame of the lamp as a visible sign, and contemplating it continually, she brought about Jhana by way of the Lambent Artifice,[5] and making that her stepping-stone, she attained Arahantship. With its fruition, intuition and grasp of the Norm were achieved, and she became especially versed in the mystic potency of transformation.[6]

And the Master, seated in conclave in the Jeta Grove, assigned her the foremost rank in the mystic powers. She, pondering the bliss of Jhana and of fruition, repeated one day certain verses. They had been uttered in anguish by a mother who had been living as her daughter's rival with him who later, when a Bhikkhu, became known as the Ganges-bank Elder,[7] and were a reflection on the harm, the vileness and corruption of sensual desires:

I.

[224] 'In enmity we lived, bound to one man,

Mother and daughter, both as rival wives!

O what a woeful plight, I found, was ours,

Unnatural offence! My hair stood up.

[225] Horror fell on me. Fie upon this life

Of sensual desire, impure and foul,

A jungle thick with thorny brake, wherein

We hapless pair, my girl and I, had strayed!'

[113] [226] The evils in the life of sense, the strong

Sure refuge in renouncing all, she saw.

At Rājagahawent she forth[8] and left

The home to live the life where no home is.

II.

Joyful and happy, she meditates on the distinction she has won:

[227] How erst I lived I know, the Heavenly Eye,

Purview celestial, have I clarified;

Clear too the inward life that others lead;

Clear too I hear the sounds ineffable;

[228] Powers supernormal have I made mine own;

And won immunity from deadly Drugs.

These, the six higher knowledges are mine.

Accomplished is the bidding of the Lord.

III.

She works a marvel before the Buddha with his consent, and records the same:

[229] With chariot and horses four I came,

Made visible by supernormal power,

And worshipped, wonder working, at his feet,

The wondrous Buddha, Sovran of the world.

IV.

She is disturbed by Māra in the Sal-tree Grove, and rebukes him:

Māra

[230] Thou[9] that art come where fragrant the trees stand crownèd with blossoms,

Standest alone in the shade, maiden so [fair and] foolhardy,

None to companion thee — fearest thou not the wiles of seducers?

She

[231] Were there an hundred thousand seducers e'en such as thou art,

Ne'er would a hair of me stiffen or tremble — alone what canst thou do?

[232] Here though I stand, I can vanish and enter into thy body.[10]

See! I stand 'twixt thine eyebrows, stand where thou canst not see me.

[233] For all my mind is wholly self-controlled,

And the four Paths to Potency are throughly learnt,

Yea, the six Higher Knowledges are mine.

Accomplished is the bidding of the Lord.

[234] Like[11] spears and jav'lins are the joys of sense,

[115] That pierce and rend the mortal frames of us.

These that thou speak'st of as the joys of life —

Joys of that ilk to me are nothing worth.

[235] On every hand the love of pleasure yields,

And the thick gloom of ignorance is rent

In twain. Know this, O Evil One, avaunt!

Here, O Destroyer! shalt thou not prevail.

NOTE. — Four gāthā's ascribed to this famous Sister are, in the Therīgatha, recorded without break. The Commentary breaks them up into four episodes. In the first, a merchant's wife at Sāvatthī, about to bear her first child in her husband's prolonged absence on business at Rājagaha, is turned out by his mother, who disbelieves the wife's fidelity. She seeking her husband, and delivered of a son at a wayside bungalow, another merchant carries off the babe in her absence, and adopts it. A robber-chief finds the distracted mother, and she bears him a daughter. This child she accidentally injures, and flees from the chief's wrath. Years after her son, yet a youth, weds both mother and daughter, ignorant of the kinship. The mother discovers the scar on her daughter's head, and identifies her rival as her own child.

[1] Iddhi.

[2] Gabbha, or matrix. So also Ang. Nik. Commentary. But cf. Dr. Neumann's note. And below, verse 257.

[3] Lotus-hued. The lengthy legend, or chain of legends, associating the past lives of this famous Therī with the lotus-flower is fully translated from the Aṅguttara Commentary in Mrs. Bode's Women Leaders, etc., J.R.A.S., 1893, 540-551. It is only interesting as folk-lore, and not as illustrating any point in her Psalm, hence is here omitted.

[4] Uposathāgāre kālavāro pāpuṇi, a phrase I have not yet met with elsewhere.

[5] See Buddhist Psy., 43, n. 4; 57, n. 2; 58.

[6] The standard description of the modes of Iddhi are given in English in Rhys Davids' Dialogues of the Buddha, i. 277.

[7] See Theragāthā, verses 127, 128. See note below, p. 114.

[8] I have read pabbaji, not pabbajiṇ, following the majority of the MSS. consulted by Pischel, as well as the Commentary. It is less forced to read, in sā, 'she,' and not 'I,' where no other pronoun follows (sā'haṇ). Verse (226) thus becomes the comment of Uppalavaṇṇā on the mother's distressful utterance.

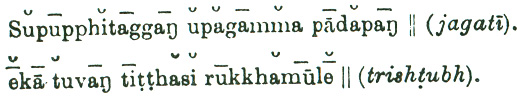

[9] The Pali metre changes here from the usual √loka to a mixed jagatī and trishsṭubh metre, but changes back again after verse 231. Cf. the other version of this Psalm in the Appendix. E.g.:

[10] Māra was himself an adept at this kind of magic (see Majjh. Nik., i. 332). I follow the Commentary and Dr. Windisch (Māra und Buddha, 139 ff.) in making the Sister speak the verse, her special gift being 'mystic potency,' or Iddhi.